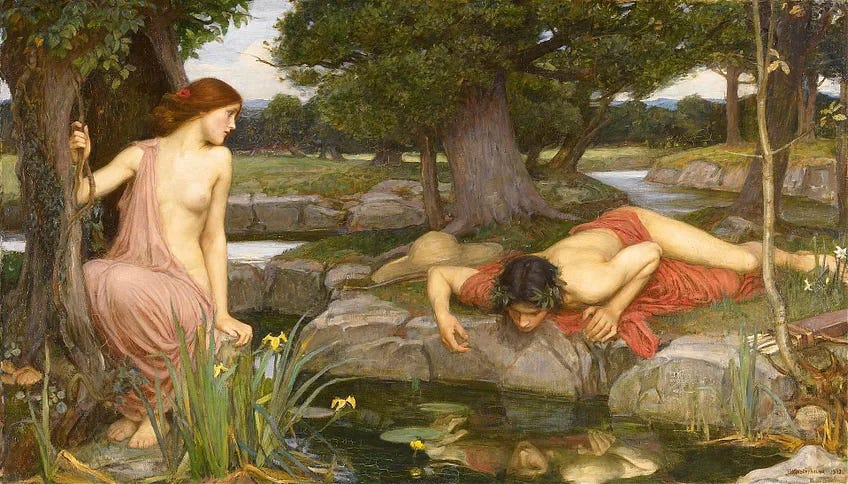

In the fourth chapter of Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Marshall McLuhan begins by pointing out that Narcissus did not fall in love with anything he regarded as himself. Yet, under cultural narcosis, we mistake narcissism for self-love, and we fail to recognize it as a form of idol worship — the worship of a false self.

The idol worshipers are all around us, within us and between us — consumed by a quest to recruit more minds and invest more energy in the worship of the Golden Calf. They don't recognize themselves as idol worshipers because, as McLuhan puts it, “self-amputation forbids self-recognition.” “Numbed” by the image, Narcissus couldn't see that he was looking at himself.

In a post on M2 Dialogue, I reflected on the beginning of the fourth chapter, and I considered possible responses to this numbness (aka alternatives to “Death through Insanity”). To catch up with the story and “get off the Optimism-Pessimism Spectrum (OPS)”, see In the Image of Its Makers: An exploration of AI, the 'Mirror World', and self-defense against the new crime of the century. Below, I continue my reading and annotation of the fourth chapter.

Media Trauma

I imagine a reader who discovers Marshall McLuhan through the fourth chapter of Understanding Media. Having heard nothing else about the author, this reader picks out UM from a bookshelf and turns to The Gadget Lover: Narcissus As Narcosis. Even if he finishes the chapter, he may not immediately understand how it belongs in a book dedicated to understanding media.

He may come up with countless hypotheses about where the central ideas of this chapter originate and where they lead, but he probably won’t fail to observe that the text of this chapter mainly deals with trauma and dissociation. Specifically, it examines a law of the sensorium through which we maintain equilibrium and regulate our response to trauma.

This is an essential theme for a book about media because — and this is the part we can’t see — the effect of media on the human psyche is fundamentally traumatic. We respond to the trauma with autoamputation and numbness. The reality is cut off from conscious awareness, and our pain is relieved.

In ‘The Medium Is the Massage’, McLuhan employs ‘massage’ as a metaphor for this process. But I believe the metaphor serves as a euphemism. Personally, I prefer to think of the process as a surgery for all the obvious and non-obvious reasons, starting with this: it involves cutting.

Whichever metaphor appeals to you, it points to what I see as the most important reality we’re not talking about. So, let’s talk about it.

Maintaining Equilibrium

We can view the technological transformation of the human subject as a massage or a surgery, but whichever metaphor we choose, it points to a reality theorized by endocrinologist Hans Selye in a paper entitled ‘A Syndrome Produced by Diverse Nocuous Agents’. This paper gave us “stress” and “stress response” as biological concepts. Here’s the abstract:

Experiments on rats show that if the organism is severely damaged by acute non-specific nocuous agents such as exposure to cold, surgical injury, production of spinal shock (transcision of the cord), excessive muscular exercise, or intoxications with sublethal doses of diverse drugs (adrenaline, atropine, morphine, formaldehyde, etc.), a typical syndrome appears, the symptoms of which are independent of the nature of the damaging agent or the pharmacological type of the drug employed, and represent rather a response to damage as such.

Selye and his colleague Adolphe Jonas pointed McLuhan to the key idea about organismic responses to “damage as such”. As McLuhan explains, Selye and Jonas “hold all extensions of ourselves, in sickness or in health, are attempts to maintain equilibrium.” And we maintain equilibrium through autoamputation. When we attempt to language this experience, our language turns metaphorical.

We may speak of “wanting to jump out of my skin” or of “going out of my mind,” being “driven batty,” or “flipping my lid.”

In response to “superstimulation”, the nervous system cuts off or isolates “the offending organ, sense or function.” For example, when the wheel extends our feet, the new intensity of the isolated function (the feet in rotation) is only bearable through numbness. Similarly, the image that Narcissus sees in the water is a self-amputation that forbids self-recognition. Self-amputation provides immediate relief and helps explain the emergence of media from speech to the computer.

The function of the body, as a group of sustaining and protective organs for the central nervous system, is to act as buffers against sudden variations of stimulus in the physical and social environment.

To maintain equilibrium, the person withdraws from threats, either through pleasure as a counter-irritant (i.e., narcosis) or comfort (i.e., the removal of irritants). With the arrival of electric technology, this self-protective process eventuates in the externalization of the nervous system.

To the degree that this is so, it’s a development that suggests a desperate and suicidal autoamputation, as if the central nervous system could no longer depend on the physical organs to be protective buffers against the slings and arrows of outrageous mechanism.

The process may seem desperate and suicidal, but it’s consistently effective in response to both physical and psychic trauma. Whether a person loses a loved one or unexpectedly drops a few feet, the event amputates the self, inducing a “generalized numbness or an increased threshold to all types of perception”.

This amputation protects the nervous system. Gradually, as the person regains normal sensitivity to sensory stimuli, he may tremble and perspire, reacting the way he would have reacted had he been prepared for the traumatic events.

The autoamputations of specific functions and senses produce equilibrium-seeking ratio adjustments across the sensory system:

Sensation is always 100 per cent, and color is always 100 per cent color. But the ratio among the components in the sensation or the color can differ infinitely.

Among examples of these adjustments, McLuhan points out that:

When nomadic man turned to sedentary and specialist ways, the senses specialized too. The development of writing and the visual organization of life made possible the discovery of individualism, introspection and so on.

The Call Is Coming from Our Media…All Our Media

Just as autoamputations can result from dropping a few feet unexpectedly or losing a loved one, they also unavoidably follow the effects of media such as the introduction of the “TV image”. These effects vary from culture to culture “in accordance with existing sense ratios”, but they invariably involve the entire field of the senses. McLuhan finds this idea expressed in Psalm 115:

Their idols are silver and gold,

The work of men's hands.

They have mouths, but they speak not;

Eyes they have, but they see not;

They have ears, but they hear not;

Noses have they, but they smell not;

They have hands, but they handle not;

Feet have they, but they walk not.

Neither speak they through their throat.

They that make them shall be like unto them.

Yea, everyone that trusteth in them.

It's reductive to speak of idol worshipers as blind or deaf or paralyzed. They are all of the above. They are numbed and, thus, protected from outrageous mechanism.

Whether we behold idols or use technology, we become what we behold. Here, McLuhan turns to William Blake's Jerusalem to gain further insight into “this simple fact of sense closure”.

What they have, says Blake, is the “spectre of the Reasoning Power in man” that has become fragmented and “separated from Imagination and enclosing itself as in steel.”

These fragmentations hurl man into “martyrdoms and wars” with his organs of perception extended so that:

If Perceptive Organs vary, Objects of Perception seem to vary:

If Perceptive Organs close, their Objects seem to close also.

How We Become ‘Servomechanisms”

Through fragmentation, we enter the “Narcissus role of subliminal awareness and numbness in relation to these images of ourselves.” We embrace our technologies and “relate ourselves to them as servomechanisms”. (I believe “servomechanism” is simply a more neutral word for a slave.)

That is why we must, to use them at all, serve these objects, these extensions of ourselves, as gods or minor religions. An Indian is the servo-mechanism of his canoe, as the cowboy of his horse or the executive of his clock.

After dropping this bombshell, McLuhan doesn’t even let the reader catch his breath. In the very next paragraph, he delivers what, to me, feels like the culminating insight in this chapter.

Sex Organs of the Machine World

As dutiful servomechanisms, we serve at the pleasure of the megamachine.

Physiologically, man in the normal use of technology (or his variously extended body) is perpetually modified by it and in turn finds ever new ways of modifying his technology. Man becomes, as it were, the sex organs of the machine world, as the bee of the plant world, enabling it to fecundate and to evolve ever new forms. The machine world reciprocates man's love by expediting his wishes and desires, namely, in providing him with wealth. One of the merits of motivation research has been the revelation of man’s sex relation to the motorcar.

Wow! As a sex organ of the machine world, I hope this message only lands where it's welcome.

Consciousness of the Unconscious

The technological extension of the human body hasn't just pushed us into “the age of the unconscious and apathy”. Ours is also “the age of consciousness of the unconscious.”

With the central nervous system strategically numbed, the tasks of conscious awareness and order are transferred to the physical life of man, so that for the first time he has become aware of technology as an extension of his physical body.

This awareness gives rise to a “social consciousness”, through which we “wear all mankind as our skin”.

Maintaining Equilibrium in the Age of Resonance

In a future post, I’ll consider special challenges in maintaining equilibrium in The Age of Resonance. I will draw, in part, on a recent essay about Why Dizziness Is Still a Medical Mystery. This inquiry is also a quest for new tools for our confrontations with such mysteries. As McLuhan wrote in The Medium Is the Massage:

Innumerable confusions and a profound feeling of despair invariably emerge in periods of great technological and cultural transitions. Our “Age of Anxiety” is, in great part, the result of trying to do today’s job with yesterday’s tools — with yesterday’s concepts.

People who choose to “contemplate what is happening” know that the process can be disorienting. I choose to metabolize these disorientations through the art of renaming and redescription. If you find value in this work, consider becoming a paying subscriber.

Miscellaneous

This post is the first draft of one of the UM chapter reviews I intend to start posting on MISM in 2024. I welcome comments and corrections based on this first draft.

I only started reading McLuhan earlier this year, and I’m just scratching the surface. I haven't even touched some of McLuhan's most important sources, such as James Joyce. Anyone interested in scratching and digging with me, stay tuned for updates about my Understanding Media Meetups in the new year.

Later tonight, and every week, you can join an exploration and celebration of the spoken word with Andrew McLuhan. See below.

.