The first chapter of Marshall McLuhan’s From Cliche to Archetype focuses on Eugene Ionesco's first play, The Bald Soprano. At the start of the chapter, we find a quote about the play from Loss of the Self in Modern Literature and Art by Wylie Sypher:

Ionesco wrote his first drama in 1948, The Bald Soprano, as a tragedy of language, using the stereotyped dialogues he found in the Assimil-method1 primer from which he was learning English. As he studied the cliches in the exercise book — “There are seven days in the week, it costs too much, I don’t have the right change, the room is too warm, where is the W.C. — he felt the text changing under his eyes: it began to ferment, he says, and he saw that these automatic colloquies represented very well the collapse of our daily lives. We go on speaking as if we were stricken by some sort of amnesia. So, Ionesco wrote his anti-play in which the Smiths and the Martins talk, talk, talk the babble that sounds, when one is really able to really hear it, appallingly like what one hears at any cocktail party. The characters disintegrate into the jargon that serves us as a way of life.

For cultures unconscious of this way of life, art serves a consciousness-raising function. And Ionesco’s absurd, McLuhan says, “is the unconscious brought up to daylight inspection.”

Pascal, in the seventeenth century, tells us that the heart has many reasons of which the head knows nothing. The Theater of the Absurd is essentially a communicating to the head of some of the silent languages of the heart which in two or three hundred years it had tried to forget all about. In the seventeenth-century world the languages of the heart were pushed down into the unconscious by the dominant print cliche. In the contemporary world the unconscious is being retrieved and brought up into daylight awareness. This is done in both private and corporate psyche. Edward T. Hall in The Silent Language reveals many of the nonverbal gestures by which whole cultures communicate. He tells us, for example, that an eight-inch interval between speakers is normal and friendly in the Arab world. Beyond eight inches it is not easy to smell one’s interlocutor. When the Arab can no longer smell his interlocutor, he stops talking and begins gesticulating. A rather similar incident occurs in The Bald Soprano when the Smiths and the Browns, in the midst of a painful English silence, meet each other for the first time. The dialogue goes: “Sniff … sniff … sniff … sniff … sniff…”

These days, we rarely get to “sniff our interlocutors”, but even without this pheromonal data, we can sense that “the Western mind is changing its mind,” and this sensation induces a “metaphysical shudder”, an “absurdist frisson”.

Ionesco particularly cultivates the art of the verbal cliche, and he uses the verbal cliche to probe one of the most fascinating phenomena of our age and that is the way in which the Western mind is changing its mind. His characteristic effect is a sort of shudder, or frisson, not unlike the metaphysical shudder which George Williamson detected in much seventeenth-century metaphysical verse. It is probable that the metaphysical shudder was related to the shift from oral to written, and it is likely that the absurdist frisson is a seismic recorder of a global shudder from new environmental technologies. The extremely mobile individual consciousness of the print-oriented man now reverses into the tribal inertia of multi-consciousness. It is rather similar to what happens when countries demobilize at the end of a major war.

The Abyss Opens Suddenly

Next, McLuhan quotes Friedrich Durrenmatt’s Problems of the Theatre to explain why The Theater of the Absurd is called ‘tragic farce’.

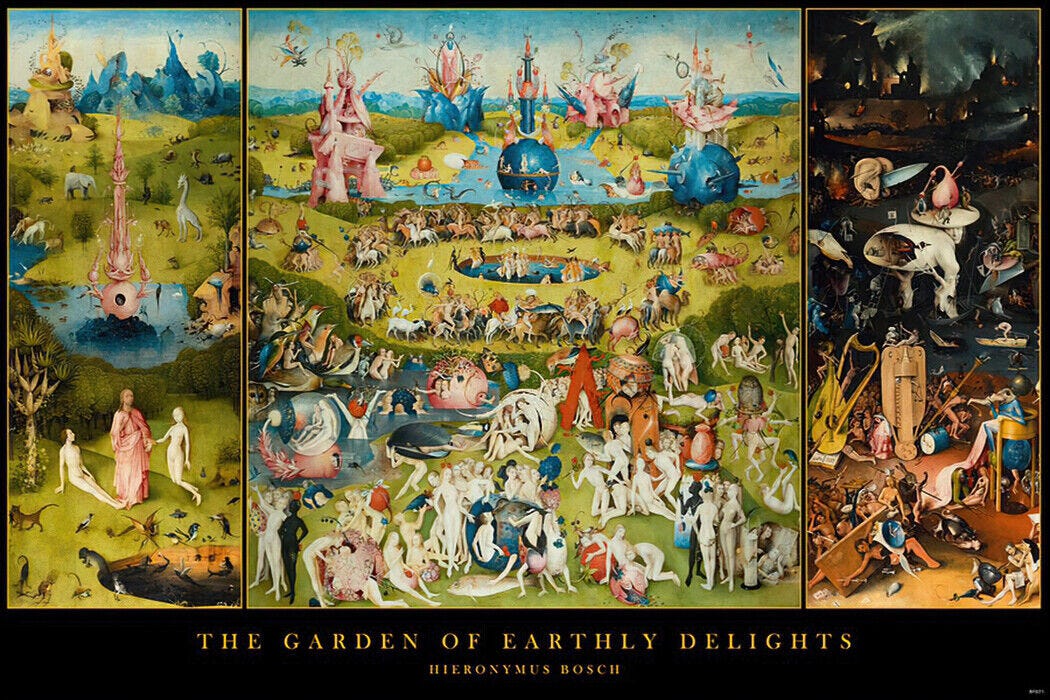

Tragedy presupposes guilt, despair, moderation, lucidity, vision, a sense of responsibility. In the Punch-and-Judy show of our century, in this backsliding of the white race, there are no more guilty and also, no responsible men. It is always, “We couldn’t help it” and “We didn’t really want that to happen.” And indeed, things happen without anyone in particular being responsible for them. Everything is dragged along and everyone gets caught somewhere in the sweep of events. We are all collectively guilty, collectively bogged down in the sins of our fathers and of our forefathers. We are the offspring of children. That is our misfortune, but not our guilt: guilt can exist only as a personal achievement, as a religious deed. Comedy alone is suitable for us. Our world has led us to the grotesque as well as the atom bomb, and so it is a world like that of Hieronymus Bosch whose apocalyptic paintings are also grotesque. But the grotesque is only a way of expressing in a tangible manner, of making us perceive physically the paradoxical, the form of the unformed, the face of a world without face; and just as in our thinking today we seem to be unable to do without the concept of the paradox, so also in art, and in our world which at times seems still to exist only because the atom bomb exists: out of fear of the bomb.

But the tragic is still possible even if pure tragedy is not. We can achieve the tragic out of comedy. We can bring it forth as a frightening moment, as an abyss that opens suddenly; indeed, many of Shakespeare's tragedies are already really comedies out of which the tragic arises.

Role-playing Areas

If “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players”, then especially since Sputnik, we live “inside the proscenuim arch of satellites,” and “the young now accept the public spaces of the earth as role-playing areas. Sensing this, they adopt costumes and roles and are ready to ‘do their thing’ everywhere.”

And What Then?

It’s been a couple of months since I first raised the question “And What Then?” For this post, an essential part of the answer comes in “Anesthesia”, the second chapter of From Cliche to Archetype.

Since Sputnik put the globe in a “proscenium arch,” and the global village has been transformed into a global theater, the result, quite literally, is the use of public space for “doing one’s thing.” A planet parenthesized by a man-made environment no longer offers any directions or goals to a nation or individual. The world itself has become a probe. “Snooping with intent to creep” or “casing everybody else’s joint” has become a major activity. As the main business of the world becomes espionage, secrecy becomes the basis of wealth, as with magic in a tribal society. Perhaps this is not the only [sic] latest form of cliche probe but merely the largest and most perceptible.

It is just when people all engaged in snooping on themselves and one another that they become anesthetized to the whole process. Tranquilizers and anesthetics, private and corporate, become the largest business in the world just as the world is attempting to maximize every form of alert. Sound-light shows, as new cliche, are in effect mergers, retrievers of the tribal condition. It is a state that has already overtaken private enterprise, as individual businesses form into massive conglomerates. As information itself becomes the largest business in the world, data banks know more about individual people than the people do themselves. The more the data banks record about each one of us, the less we exist.

Next Year

In difficult times, my people like to imagine that, next year, we will reach Jerusalem, but translations of this metaphor into matter continue to inspire new scenes in the global theater of absurdity.

These scenes don’t just unfold in geopolitics. For example, the second chapter of From Cliche to Archetype concludes with a quote from a letter written by Sigmund Freud to his beloved Martha:

Woe to you, my Princess, when I come. I will kiss you quite red and feed you till you are plump. And if you are forward, you shall see who is the stronger, a gentle little girl who doesn’t eat enough or a big wild man who has cocaine in his body. In my last severe depression I took coca again and a small dose lifted me to the heights in a wonderful fashion. I am just now collecting the literature for a song of praise to this magical substance.

There you have it — another pursuit of a “magical substance”, another metaphor of liberation that inevitably leads to absurdity.

110 Years Ago

Albert Camus was born on this day in 1913. In celebration of the occasion, I offer you this quote selected by Poetic Outlaws.

“It is the failing of certain literature to believe that life is tragic because it is wretched. Life can be magnificent and overwhelming – that is its whole tragedy. Without beauty, love, or danger it would be almost easy to live.”

###

Housekeeping

It’s been nearly a year since I returned to Substack. In countless ways, the journey has been deeply gratifying, but I’ve also observed the twitterization of Substack and the ubiquity of folks on this platform who, in McLuhan’s words, “snoop with intent to creep”. As an initial adjustment to these trends, I converted End of Theory (EoT) to a private Substack to protect my IP related to “Bullshit Conversion”. You can learn more about private Substacks here.

From Wikipedia: Assimil (often stylised as ASSiMiL) is a French company, founded by Alphonse Chérel in 1929. It creates and publishes foreign language courses, which began with their first book Anglais Sans Peine ("English Without Toil"). Since then, the company has expanded into numerous other languages and continues to publish today.