After the impossible diagnosis in Chapter One, the Elephant's attention inevitably turns to the impossible mission: treatment without diagnosis. Using the language of Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey, we can think of this moment as a call to adventure that the Elephant may follow or decline.

Non-allegorical human beings who reach this moment generally decline the invitation. Frequently, the tone of their reply brings to mind a scene in As Good As It Gets, the 1997 film about Melvin Udall (Jack Nicholson), an obsessive-compulsive, germophobic writer of romantic fiction. When offered to wear a restaurant's jacket and tie to comply with the dress code, he rejects the courtesy emphatically: "In case you were going to ask,” he declares, “I'm not going to let you inject me with the plague either!"

The vehement rejection of the impossible mission may be rude, but it's also perfectly understandable. Just as the diagnosis defies description, so does the mission. Both require a liberation from anxiety and a certain level of comfort with the terra incognita beyond the limits of language.

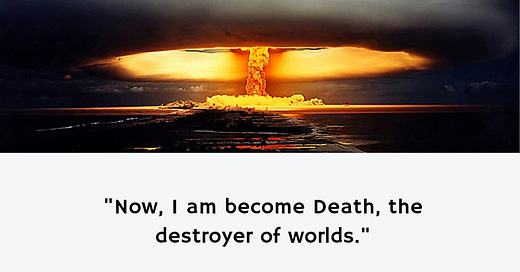

I'll to start this chapter with a few cartographic observations about this liminal space. Then I'll turn to four thought-provoking sources for advice on the war that begins if the Elephant follows the call to adventure. At the end, I will return to the discussion I started in Chapter One about Robert Oppenheimer's 1945 introduction to this war.

Beyond Language

Every day, we step into a river of experiences that transcend the limits of language. By default, we treat these departures from comprehensibility with an adaptation of the ‘Vegas Rule’: what happens beyond the limits of language stays beyond the limits of language. That’s what we’d like to believe.

With this bit of sloppy sophistry, we justify leaving the inexpressible not only unexpressed, but also unexamined. But if we reflect for even a moment, we realize that the Vegas Rule is bullshit. Whether we apply it to decadent pursuits or refined enthusiasms, the rule is false and useless. What happens in ‘Vegas’ never stays there.

Why the 'Vegas Rule' Is Bullshit

The persons who bear witness to the happenings ‘in Vegas’ often find their lives re-colored by the memories of this liminal space. In moments of self-honesty, the newlywed husband, now back home, may remember that his bachelor party revealed or re-ignited his doubts about marriage. His wife may remember the version of herself now concealed by the cloak of sobriety.

The moment of clarity may pass. The echoes of Vegas may fade. The couple may return to the choreographed normalcy of the lives they allow into consciousness. But, to paraphrase the Gladiator, what happens in Vegas echoes in eternity.

Privately and publicly, we may reasonably debate when we arrive in Vegas and when we return to normal life. Historians may argue, for example, that America landed in Vegas on November 8, 2016 — Election Night — or they may trace the start of this trip to the crash of 2008 or the tragedy of 9/11 or to the start of the Nuclear Age in 1945 or to another watershed moment. Regardless of how we construct the chronology of this trip, sooner or later, we confront what this trip has revealed.

Through the Membrane of Consciousness

Due to the nature of the revelations, we may resort to psychological defenses. We may deny, suppress, trivialize and disown the realities percolating into consciousness. It’s not necessarily because we lack courage or intelligence. It’s that we lack the symbols to language the revelations.

However, psychological defenses do not form an impenetrable wall around the limits of language. Instead, they form a semi-permeable membrane. Both in living cells and in the human psyche, this membrane arguably performs the most important function. Forming a filter between the inner and the outer space, the membrane honors the separation without fetishizing it. It absorbs and oozes information, distinguishing the nourishing from the toxic.

The membrane has a wisdom tragically lacking, for example, among the red-and-blue participants in the farcical border-wall debate now faded from public discourse. The wisdom of semi-permeability also seems absent from all the pseudo-controversies around false dichotomies that energize modern tribalism.

For those with the eyes to see and ears to hear, the membrane forming a filter around the limits of language translates the information flowing in from the other side. The data that survives the crucible of translation trickles into conscious awareness.

For example, all poetry worthy of the name is a way of speaking about the unspeakable. Every tear is a drop of meaning flowing into comprehensibility. Every moment of aesthetic arrest is an intimation of the inexpressible. Every dream is a letter from Self to self begging to be read. Every inspired action is a message from the other side. Every bite of a psilocybin mushroom is a cleansing stroke applied to the doors of perception.

This essay is one man’s record of the messages now flowing across the membrane — messages so fragile, nuclear, equivocal or esoteric that most of them may float in the synaptic cleft for years before we start seeing them acknowledged in blog posts, white papers, opinion columns and political speeches.

Like fragments of a dream, these messages cannot be asserted or debated. They are best spoken and heard through whispers. Turning to Gladiator again, recall the words of Marcus Aurelius addressed to Maximus:

There was once a dream that was Rome. You could only whisper it. Anything more than a whisper, and it would vanish. It was so fragile. And I fear it will not survive the winter. Maximus, let us whisper now together…you and I.

Where Matter Meets Metaphor

Not everyone likes to speak or be spoken to the way Marcus Aurelius spoke to Maximus. When poetry, metaphor or psilocybin carry stories beyond the limits of language, not everyone stays on for the ride.

For the people drawn to the comfort of the languageable, the story ends here. The Hero declines the call to adventure. The Israelites enslaved in Pharaoh's Egypt dismiss the idea of Exodus and rededicate themselves to their daily labor. The mind, driven by the will to survive, recoils from the invitation. The liminal space where matter meets metaphor dissolves into the horizon of relevance.

But sometimes the Hero rises to the challenge, and he finds himself at war against enemies foreign and domestic. He fights a war he can neither describe nor abandon.

Introduction to the Elephant’s War

The Elephant's war hardly shows even a superficial resemblance to traditional conceptions of war. Speech is the Elephant's main weapon, and the attacks against him usually pose no threat to his biological survival. His adversaries are everywhere and nowhere. On every front, the Elephant feels tangled up in irreconcilibilities.

He understands the all-consuming epidemiology of blindness, but he can't opt out of using his BGs. More than ever before, the Elephant is conscious of himself as a citizen and beneficiary of the very system he is fighting. Depending on circumstances, the Elephant may feel like a dissident.

Desperate for liberation from the cage of fractal falsehood, the Elephant finds that every exit sign marks a false exit that leads back to the cage. The Elephant is exhausted by failed Shawshank redemptions.

The Elephant's best description of his predicament is that he is undergoing a self-directed treatment without a diagnosis. Less and less inclined to view this predicament with shock or disbelief, he knows he can no longer turn back. His treatment is a war — his Mahabarata and Kurukshetra.

The Elephant finds pleasure in reading and writing about the strange forms and complex dimensions of his war. He marvels at the ease and frequency with which he steps from the hypercomplexity of his Nuclear Moment to the choreographed normalcy of his ordinary life. Practicing what Buddhist teachers preach, he remembers not only his Buddha nature, but also his zip code.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna turns to Lord Krishna for counsel, and the Elephant, too, turns to his sources. In this chapter, they include:

James Hillman, particularly his talks about our Terrible Love of War and Myth and the World Around Us.

Chris Hedges, particularly his book War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.

Marshall McLuhan, particularly his thoughts on Violence as a Quest for Identity.

Georgio Agamben's essay on Atomic Warfare and the End of Humanity.

At some point, I will schedule a session with the ghost of Carl Philipp Gottfried von Clausewitz to delve into his book On War.

Advice from James Hillman

Distinguish mythology from myth. The former refers to a genre of storytelling. The latter refers to life fueled by the stories ingrained in the psyche. In the past, you turned to "dead poets", including me, to study mythology. Now you need to write your own gospel and live your own myth.

Writing for an external audience will help. In fact, given the sociopolitical dimensions of your war, you can no longer afford to only write for your internal audiences. But writing for yourself remains foundationally important. Your inner clarity will radiate through your external messages.

Think about the idea of "self-authoring" – of course without fetishizing the existing maps of this idea in academic psychology. Think about the idea itself – your experience of this idea – not other people's definitions and systematizations.

Your story is your weapon, and at war, you must neither hesitate to use your weapon nor rush to use it. Always hasten slowly.

Never lose sight of the balance between the internal and external orientation. Also maintain a balance in your temporal orientation. You've lived most of your life without thinking seriously about these dimensions of your Becoming. It's time to catch up.

More than anything, observe your own actions to discern the patterns they manifest. These patterns are your story. Hone your tools of observation with the patient care and attention of a warrior sharpening his sword in preparation for battle. Regularly inventory your arsenal, your portfolio of tools, including dream analysis, journaling, reading (bibliotherapy), self-publishing, and of course, Dialogue and Active Imagination.

You may also want to take a fresh look at your relationship with the Warrior archetype. Even though Robert Moore has spoken unkindly about me, his talks about the Warrior may help.

If you heard my message about the Terrible Love of War, you understand both the impossibility of talking about war and the harm of talking about war reductively. Your war may seem primarily “psychosocial” at times, but never lapse into the hubris of "cartographic fundamentalism". The dimensions of war are complex; treat all cartography with meta-skepticism.

You started to think of violence as a quest for identity, heroic action, and self-transcendence. Do not hold back. But always stay grounded. Remember the pitfalls of liminality.

Secularists and religionists have colluded to propagate the “fake news” that the gods have fled as modernity has consumed our world. In fact, the gods are with us as facts of everyday life, not as the glorious and frightening figures depicted in Joseph Campbell’s massive mythographic treatises.

After resurrecting gods as facts of everyday life, ask yourself if gods can ever flee. And who benefits by answering this question in the affirmative? Who wants the gods gone? Who wants a world littered with soulless objects?

The beneficiaries are not only the secularists eager to exploit the declaration that gods have departed. Christianity exploits this declaration too by inserting Jesus into the newly created absences. Notice also that pagan deities still survive as disguised presences within the Christian mythos, inviting recurring attempts to revive these sleeper cells.

I'll conclude here by reiterating my advice from a decade ago: Pay attention to your symptoms. Let these two quotes help you stay attentive to these messages:

Called or not called, the gods will appear. (Vocatus atque non vocatus Deus aderit) — Delphi

The gods have become diseases. Zeus no longer rules Olympus but rather the solar plexus and produces curious specimen for the doctor’s consulting room or disorders the brains of journalists and politicians who unwittingly let loose psychic epidemics in the world. — Jung

Think further about the psychologization of the pantheon, the interiorizations of divinity, and the move from transcendence to immanence. In moments of confusion, consult the sources: Baruch Spinoza, Heinrich Zimmer, Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell.

As Jung argues, the modern age has interiorized gods into pathology. Residing in the psyche, they now bear new names and function as causes of the soul’s infirmities. Thus, the repressed returns, called or not, in the strangely inventive form of symptoms that afflict us as we wait for the light to change at the corner of Broadway and 42nd.

Advice from Chris Hedges

You don't need to read my book to understand what Plato meant when he said: "Only the dead have seen the end of war." War is hell, and it ends with death.

It's easy to remember this truth when you are conscious of yourself as a warrior in the midst of battle. But this truth is easy to forget after you consume whatever opium of the masses you choose on any given day to numb yourself to this knowledge.

It feels strange to you to shift so frequently from the ineffability of war to the choreographed normalcy and tedium of daily life, because the rush of battle is a potent drug that scrambles the very structures of meaning on which your daily life depends. Viewed through the fog of war, these structures appear as lies.

But war doesn't just destroy meaning. It also creates meaning. In fact, it creates a higher meaning compared to the meaning it destroys. That's why, at war, you feel elevated. Like a religious conversion, "war makes the world understandable – a black-and-white tableau of them and us."

The ancients knew that war is a god whose worship demands human sacrifice and an embrace of violence as a rite of passage. Today we're uneasy about God and gods, but war is one of the experiences that confront you with the reality behind these words.

You struggle with the ineffability of your war, and I urge you to stop struggling. You struggle in vain. You will never find the language you seek. No language will transport you to the realm beyond language. I know that you know this, but now you must live in the light of this knowledge.

You also know that we lose sight of some important truths not because they are ineffable, but simply because we forget them. So here's a reminder for you:

Just remember,' a Marine Corps lieutenant colonel told me as he strapped his pistol belt under his arm before we crossed into Kuwait, 'that none of these boys is fighting for home, for the flag, for all that crap the politicians feed the public. They are fighting for each other, just for each other.

So, who are you fighting for?

Advice from Marshall McLuhan

Perhaps the most comforting message you can extract from the video linked above is that your war isn't yours. It is merely your battlefield in the wars that inescapably flare up as citizens of the Global Village pursue their quest for identity. You are not alone. What's unique about your participation in this war is also what's unique about every warrior's participation in this war: it's how you talk about it, if you talk about it at all.

You already know about both the savagery of the Global Village and the range of your self-expressive capacity. You know that all forms of violence are a quest for identity. You know that when you live on the frontier, you have no identity, and you turn to violence to become somebody. You know that identity is always accompanied by violence.

Instead of dwelling on these concepts as concepts, notice the comment towards the end of the video (starting at 5:10): Literacy both immunizes and makes you more vulnerable to propaganda. The literate man is a natural target of propaganda; you can't propagandize a native.

But to appease the literate man within you, try asking ChatGPT to "Summarize Marshall McLuhan's views of violence as a quest for identity."

Marshall McLuhan believed that violence is a form of expression used by individuals and groups to assert their identity. He argued that the use of technology and media can amplify and spread violent acts, making them more visible and impactful in shaping group identity. McLuhan also believed that the increased speed and interconnectedness of modern technology can create a global village in which the actions of individuals and groups have a greater impact on the collective identity and consciousness of humanity. Therefore, he saw violence as a quest for identity in a rapidly changing technological landscape.

Advice from Georgio Agamben

In any war, it helps to know your weaknesses – especially if there's a specific Achilles Heel. For people drawn to intellectualization as a defense mechanism, it's natural to react to the essay above by incorporating it into an ongoing bibliotherapeutic project, which would mean delving deeper into the cited sources such as Karl Jaspers and Maurice Blanchot.

Nothing wrong with bibliotherapy, but like war, it is a lifelong project, and it works best when anchored in an awareness of its limitations. Even with the AI-fueled increase in the typical reader-writer's processing capacity, the use of bibliotherapy during wartime requires new forms of reading and writing.

The most important characteristics of these new forms include:

They are non-academic, and Marshall McLuhan can tell you more about that.

They are highly experimental, or in McLuhan's language, they are "probes".

Intellectualization is more likely to lead to “anodyne and vain aspirations that leave intact the principle responsible” for the problem. Also, intellectualization begins and ends in language. It is not a warrior's defense.

I highlight two messages from my essay that seem to resonate the most with the editorial mission/obsession of M2 Dialogue. First message is contained in the title of Blanchot's essay: The Apocalypse disappoints, certainly when you study it only with language.

The second message is contained in what Blanchot wrote about…

“…a simple fact about which there is nothing to be said, except that it is the very absence of meaning, something that deserves neither exaltation nor despair and perhaps not even attention.”

Your war is an attack against an absence.

The Elephant's Manhattan Project

Heartened by the advice of the sages, the Elephant refocuses on his war. To help the Elephant, I started by watching this documentary about the history of the Manhattan Project.

The advent of the Nuclear Age intrigues me, but not mainly as a milestone in the evolution of the technology of war. As an innovation, nuclear technology had a major but also merely quantitative effect on the consequences of war. It increased the scale, speed and ease of destruction.

But the Nuclear Age fascinates me mainly because I think about it as the highest and most radically perverted expression of the human desire for peace.1 I see the advent of the Nuclear Age as a milestone in the use of war to end war and the conflation of this outcome with peace.

In this framing, Robert Opperheimer's famous quote from the Bhagavad Gita – I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds – suggests something fairly obvious already covered by the sages above:

We only find peace when we cross the threshold of death.

The Apocalypse Disappoints.

The Elephant's Manhattan Project is also codenamed "Project X", and even if it begins with this disappointment, it certainly doesn't end there. Standing on the shoulders of giants, the Elephant observes the horizon of meaning and continually re-theorizes the topology of his Battle of Kurukshetra and his technological arsenal.

More Advice for the Elephant

Focusing on the Elephant's latest observations, the next chapter will introduce the "Cocktail Theory” of peace. Here, the Elephant's story starts to shift from "Naming the Problem" to "Naming the Cure", and it will continue as part of my second book.

I will return to the first book to introduce other characters in need of better names for their problems. Current candidates include:

The boiling frog.

The turtle (or frog) stung by a scorpion.

The canary in the coal mine.

The moth drawn to a flame.

The scapegoat.

The slave.

Example of enantiodromia